[Don’t miss the the first and second parts of this post]

Charlie Patton recorded 57 songs between 1929 and 1934 which sold exceptionally well and catapulted him into relative stardom. His legacy lives on, 80 years after he stopped doing so. Even though he has not stayed a household name, latter-day artists cite him as a major influence, from Bob Dylan to Led Zeppelin and The White Stripes. The reason he has endured at all is because Patton was a self taught genius who worked out the blues for himself with little help from others. That’s not to claim that he invented the genre. musical movements tend to emerge as parallel lines of development converge. We can see that from the use of blues as a term to describe sadness from very early on, across the whole of the Mississippi area,

I laid in jail, back to the wall

Brown skin gal cause of it all

I’ve got the blues, I’m too damn mean to talk

A brown skin woman make a bull-dog break his chain.

Those lyrics from the Journal of American Folk-Lore are similar to these collected by folk music researcher Howard Odum before 1909, “I got the blues but too damn mean to cry” and “I got the blues and can’t be satisfied / Brown-skin woman cause of it all / Lord, Lord, Lord.” Slightly earlier, composer-publisher Antonio Maggio said he heard a 12-bar tune called “I Got The Blues” played by a guitarist in Louisiana in 1907.

The first bluesman Patton likely heard was Lem Nichols who sang “rag” ditties including ‘Spoonful’ and ‘Pearlee’ using a pocket knife as a slide. Even though he was about fifty years old when Patton heard him, suggesting the blues stretched back well into the heart of the 19th century, Charlie Patton is considered the beginning because, apart from Blind Lemon Jefferson’s country style, Patton’s is the earliest blues recording that we have, and the oldest recording of true Delta blues that tells us about its source. Within his single chord licks you can hear all the rhythms and expressions that would develop, with an extra phrase here, a key change there, into the form carried off the plantations and up to Chicago by greats like Muddy Waters. It’s this lineage from before Patton, that was then handed on through his recordings, to rock and roll bands during the 1960s blues revival, and the 1970s stadium-filling groups playing blues rock. A great example is Willie Dixon’s ‘Spoonful’, which he loosely based on Patton’s ‘A Spoonful Blues’, which was first recorded by Howlin’ Wolf in 1960 and became a staple song within the underground blues boom in the UK in the sixties. Most famously of all must be Cream’s reworking of the track in 1967, but it was also picked up by Ten Years After, Etta James, George Thorogood and The Grateful Dead.

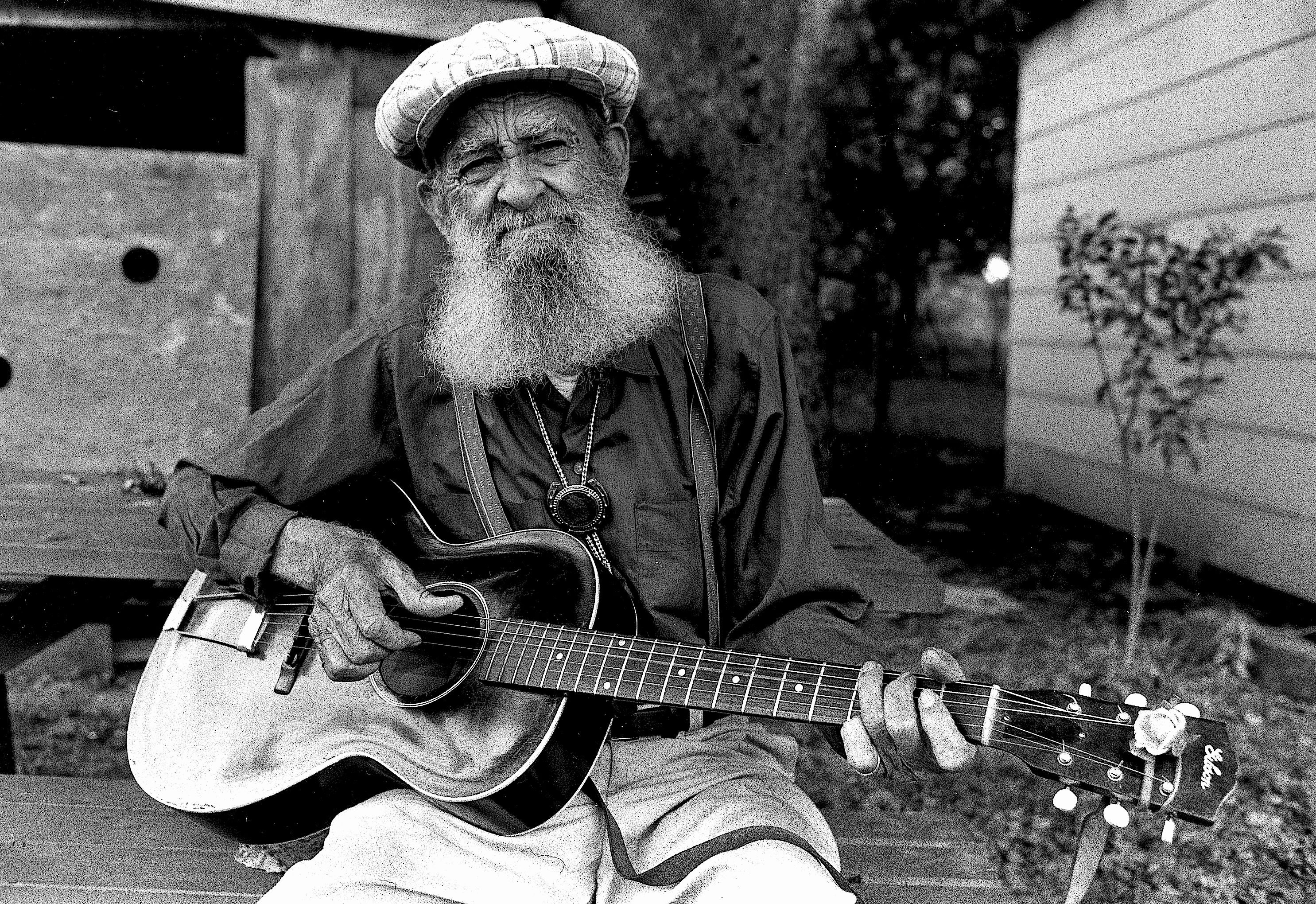

Analysis of Patton’s playing has shown that he must have played most, if not all, of his songs lap style. Doing so enabled him to make long slides up as far as the 17th fret in say ‘Magnolia Blues’, where holding the guitar “normally” necessitates an uncomfortable stretch around the bottom edge of the soundboard’s upper bout. In later years, cutaway models would facilitate access to these highest pitches, but Patton likely played a black Stella, with a pearlette-white fingerboard made by the Oscar Schmidt Company. They had their headquarters in Jersey City, and were considered the “the world’s largest manufacturer of fretted musical instruments”, up until the Wall Street Crash of 1929. According to an account given to Gayle Dean Wardlow by the Reverend Pearly Brown, who knew Patton personally, the “Tefteller” portrait, being the only photograph we have of him, shows Patton seated holding a Stromberg-Voisinet parlour guitar. However, it is widely believed that the guitar in that picture is simply a prop, not Patton’s own instrument at all. Even so, he is indeed holding it flat enough to fret a chord from above. Although the arguments are persuasive, we have to remember that he was also famous for his showmanship and performance antics, playing behind his head, through his legs, riding the guitar like a mule, possibly playing with his teeth too. So he was obviously able to pick out his tunes from a variety of positions.

The sort of guitar he did play would cost less that $10 (equivalent to $125 today). In context, a plantation wage was 50 cents to a dollar, per day, but bluesmen would earn a weeks wage, five dollars for a single night’s work. New instruments, whiskey, cigarettes, fine clothes, stetson hats, automobiles and fêting their female company, would all put high demands on that income, yet as Bessie Turner recounted, Patton never seemed short of money.

It’s thought that bluesmen probably included the hit tunes of the day in their repertoire. After all, that’s what their audiences would have wanted to hear, as well as their own songs. So, it’s likely Patton would have been proficient in various Vaudeville and Tin Pan Ally tunes. But it wasn’t these previously recorded songs that any recording company would be interested in. They didn’t want cover versions, but original blues and spirituals. With growing fame, Patton decided he was ready to record. He wrote a letter to a white man named H.C. Speir, a storeowner in Jackson, Mississippi, and free-lance music scout for several northern labels, including Paramount Records, “The word was out all over Mississippi: If you want to get on record, you go audition for Mr. Speir. The word was he won’t cheat you”. Spier actually visited Dockery’s and was soon collecting his spotting fee for putting Patton on a train to go the 750-miles to Indiana. Spier’s judgement would be proven correct, “Patton was one of the best talents I ever had. And he was one of the best sellers, too, on record.” Patton would have been paid a flat fee for each song, usually about $40, which explains his sacks of money and comparative wealth.

Patton would have arrived into the grand Pennsylvania Railroad Station at North 10th Street and North E Street, downtown Richmond. On June 14, 1929, 38-year-old Charlie Patton walked into the backroom studio to the rear of a warehouse, next to some railtracks, with his Stella guitar. The Gennett (pronounced with a soft ‘g’ as in giraffe) Records studio would that day host a most prolific day in Delta blues recording, intermittently interrupted by a train rolling past. How long it took to cut all the sides from this session, we don’t know, but if he stayed in town then it was probably in ”Goose Town,” the shanty neighbourhood, north of the station. Here Gennett staff often accommodated their black recording artists.

Paramount had recorded in Chicago since 1920, but in early 1929 decided to create a studio at their headquarters in Grafton, Wisconsin. The deal with Gennett was a temporary arrangement while the building was being completed. Gennett therefore ended up producing the first sides by Patton, and the last records of Blind Lemon Jefferson. In an odd twist, Gennett was only able to keep going through a more lucrative “private” or “vanity” recording sideline, and one of their biggest customers was none other than the Klu Klux Klan who commissioned records in thousands for their membership, such as, ‘The Fiery Cross’ and ‘Wake Up America Kluck Kluck Kluck’. In 1923, Louis Armstrong made his legendary, first ever recording as part of King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band at the studios, just before a Klan orchestra was in the same studio, using the same engineer.

Paramount released the 14, 78-rpm shellac sides recorded by Patton under three names: Charley Patton, Rev. Elder J.J. Hadley, and the rather fanciful Masked Marvel. Sales were modest at first, compared with mainstream artists, but suddenly, the Mississippi Delta had been put on the musical map, and within 5 years, Patton became the largest selling blues artist of his generation. The 14 songs were,

Mississippi Boweavil Blues, Screamin’ and Hollerin’ the Blues, Down the Dirt Road Blues, Pony Blues, Banty Rooster Blues, It Won’t Be Long, Pea Vine Blues, Tom Rushen Blues, A Spoonful Blues, Shake It and Break It (But Don’t Let It Fall Mama), Prayer of Death – Part 2, Prayer of Death – Part 1, Lord I’m Discouraged, I’m Going Home.

Moving to the new Paramount studios at Grafton in October, he recorded twice as many as before,

Going To Move To Alabama, Elder Greene Blues, Circle Round The Moon, Devil Sent The Rain Blues, Mean Black Cat Blues, Frankie And Albert, Some These Days I’ll Be Gone, Green River Blues, Hammer Blues, Magnolia Blues, When Your Way Gets Dark, Heart Like Railroad Steel, Some Happy Day, You’re Gonna Need Somebody When You Die, Jim Lee Blues Part 1 & 2, High Water Everywhere Part 1 & 2, Jesus Is A Dying-Bed Maker, I Shall Not Be Moved, Rattlesnake Blues, Running Wild Blues, Joe Kirby, Mean Black Moan, Farrell Blues, Come Back Corrina, Tell Me Man Blues, Be True Be True Blues.

In June the following year, only 4 sides were laid down,

Dry Well Blues, Some Summer Day, Moon Going Down, Bird Nest Bound.

and it would be another four years before he would make it back into a studio, this time a dozen songs for Vocalion Records, based in New York City,

Jersey Bull Blues, High Sheriff Blues, Stone Pony Blues, 34 Blues, Love My Stuff, Revenue Man Blues, Oh Death, Troubled ‘Bout My Mother, Poor Me, Hang It on the Wall, Yellow Bee, Mind Reader Blues.

Patton’s recording legacy is extraordinary in elevating the blues idiom to a whole new level and many of these tracks have attained legendary status. The recordings suffer from the low quality shellac reproduction dynamics, but in one way this adds to their antiquity and charm, but in another, frustrates a relaxed listening experience. As the Gomez song goes, “I spend a lifetime / Trying to decipher / Charlie Patton Songs / I don’t know why I bother / Even if I think it’s right / It always comes out wrong”. Ethnomusicologist Jeff Todd Titon notes in the book Shadows in the Field how he had sat with Patton’s friend Son House, trying to get him to decipher the lyrics from a tape recording. Rather than attempt it, House instead reminisced about how “Papa Charlie” got religion in the old days in the Mississippi Delta and how they had made bad moonshine whiskey together, inevitably ending up in a scrape with the law. As a case in point, ‘Banty Rooster Blues’ is delivered with a drawl that masks its message as a celebratory and defiant song, with a cryptic hint of sex, as we saw in ‘Easy Rider’ before, “My hook’s in the water and my cork’s on top / My hook’s in the water and my cork’s on top / How can I lose, Lord, with the help I got / I know my dog anywhere I hear him bark / I know my dog anywhere I hear him bark / I can tell my rider if I feel her in the dark“.

‘Mississippi Boweavil Blues’ has that gravelly but light tenor, fantastic double strum on the bass notes, like a drone humming while a bottleneck intermittently spikes up through the depths. It’s a blueprint for punk rock as much as the blues. ‘Screamin’ and Hollerin’’ has more of a countrified feel with stepping down bassline and light strum across the mid- to treble strings this time. Patton seems to be establishing two styles depending on what he assigns to the rhythmic part of his songs and what is reserved for intonation, to follow his voice for the chorus, or accentuating significant lyrical lines. ‘Down the Dirt Road Blues’ has a counter rhythm tapped out on the guitar body to give his country blues style an additional layer.

Patton also covered several songs, but would usually modify something about them to make them his own. The most recognisable example is his hit ‘Some Summer Day’, which uses The Mississippi Sheiks million bestseller ‘Sitting On Top of the World’. The melody was left unchanged but “But now he’s gone, I don’t worry / Because he still has chance number three.” replaced the famous refrain, “But now she’s gone, I don’t worry / I’m sitting on top of the world”.

Singing a much modified version of the popular Tin Pan Alley song ‘Some of These Days’, Patton’s booming drawl makes the tellurian lyrics about love and loss sound hymnal, even dirge-like, “Some these days, you’re gonna be sorry / Some these days, I’m going away / Some these days, you’re gonna miss your honey / I know you’re gonna miss me, sweet dream pie, be going away”. It departs dramatically from the the earlier 1911 recording by ex-Ziegfeld Follies, Music Hall singer Sophie Tucker. Her version of the song written by Shelton Brooks is a mid-tempo show tune run through with an arabic swirl. It also differs markedly from Patton’s reading because he discarded the context-setting preamble that Tucker half-spoke to introduce the sweetheart protagonists and explain the circumstance of their parting. It’s clearly a highly malleable song, recorded by Tucker (1911), as well as the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1923), Art Landry and His Call of the North Orchestra (1923), Ted Lewis and His Band with Tucker again (1926), Vaughn De Leath (1927), Ethel Waters (1927) and Louis Armstrong and His Orchestra in the same year as Patton. By the time Bobby Darin recorded it as a big band ragtime number in 1959, while the verse-chorus structure remained essentially the same, the lyrics and styling have been changed again so that it is barely recognisable as the original.

Of note is how Patton adapted the song, retitled ‘Some These Days I’ll Be Gone’, by introducing lyrics to change the rhythmic structure, rather than simply accentuate a different note, as was the case for Tucker and Darin. The verses of the three versions show the effect of elongating the last line with the effect of introducing tension, until it is released on the final note.

[Tucker]

Some of these days You’ll miss me, honey,

Some of these days You’ll feel so lonely;

You’ll miss my hugging, You’ll miss my kissing,

You’re gonna miss me, honey, when I’m faar away.

[Darin]

Some of these days You’re gonna miss me, baby

Some of these days You’re gonna feel you’re so lonely

You’ll miss my huggin’ You’re gonna miss my kissin’

You’ll miss me, baby When I am far awaaaaaaaay

[Patton]

Some these days, you’re gonna miss your honey

Some these days, I am going awaaaaaaaaaaay

Some these days, you’re gonna miss your honey

I know you’re gonna miss me, sweet dream pie, be going away

Extending these lines, Patton is stretching and moulding the chord sequence of the original into the basic structure of a 12-bar blues. Another example of this is his ‘Banty Rooster Blues’ recorded in the same year,

I’m going to buy me a banty, put him in my back door

I’m going to buy me a banty, put him in my back door

Lord, he sees a stranger coming, he’ll flap his wings and crow

Here Patton has gone one stage further and collapsed the first lines into a repeated single phrase. The classic “I woke up this morning…” formula.

One of the devices that allows him to stretch and bend the chord structure so much is a repeating bass signature. Sam Chatmon (below) remembered that Patton only knew how to play in two tunings, E and open G, also known as “Spanish”, although fingerstyle guitarist John Fahey also identified songs in the keys of F and C, as well as the key of D played in an open D tuning. In the case of ‘Some These Days I’ll Be Gone’ with that lovely gospel melody, in the key of E major, the unfretted bottom E string acts like a drone, anchoring the rhythm and melody to the root note. Tension results by moving away from the root towards another significant note, defined by the matching scale, or mode (Patton uses the Ionian here). The note most often used is the dominant. B is the dominant of the E ionian mode.

In pop music, a jump to the dominant or subdominant, is often used to introduce a change in the song’s energy. It’s the bit where the key changes, it’s proper name is modulation, and the singer in the video looks like they’ve strained something. In these oldest blues, also known as primeval blues, instead of changing the key, the dominant is used only briefly to establish tension within the musical progression. A popular chord to play at this point is a 7th. It sounds real bluesy. Later, Patton and others would add another chord, also often a 7th to give us the 12-bar blues progression that has been used thousands and thousands of times during the last century. His ‘Moon Goin’ Down’ and ‘High Water Everywhere’ are great examples of this.

The perceptive W.C. Handy had noticed this flavouring of the southern music during his travels, and imitated it to give his own compositions a bluesy sound,

The primitive southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor. Whether in the cotton field of the Delta or on the Levee up St. Louis way, it was always the same. Till then, however, I had never heard this slur used by a more sophisticated Negro, or by any white man. I tried to convey this effect … by introducing flat thirds and sevenths (now called blue notes) into my song, although its prevailing key was major … , and I carried this device into my melody as well … This was a distinct departure, but as it turned out, it touched the spot.

Today we have the luxury of perspective, broadened by immediate access to the world’s musics, and deepened by archival research, literally rooting out the stories of their development. We can now compare the lineages of African blues by the likes of Ali Farka Touré and American blues and conclude that the significant difference is the absence of a 12-bar progression entirely, with a stronger reliance on rhythmic and polyrhythmic components to shape the music. It is then possible to suggest and test a rhythmic connection to a development within another musical movement, the modal form that George Russell, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, etc., did so much to progress in Jazz music. This is why the blues can be claimed to underlie modern music, and those pioneers of the primitive blues are the start of it all. Charlie Patton would probably not be able to discern his Delta blues in Davis’ sublime ‘Freddie Freeloader’, even though it is a 12-bar blues, nor in Cream’s rollicking version of ‘Spoonful’. But, with the benefit of hindsight, we can. So, while Charlie Patton wasn’t necessarily the inventor of the Delta blues, he was the first to put on record what it sounding like in its early days. His recordings have proven to be a benchmark for all that followed, and an invaluable reference point worth a king’s ransom, and deserves the type of respect usually reserved for royalty.